By Lucia Nagler

Published 9/20/2022 6:23 am PST

Updated 9/20/2022 2:00 pm PST

Just last Fourth of July, the City of Pomona hosted Unity Day LA. It was a day marked by festivities and fundraising, and it began with the unveiling of black woman artist Manuelita Brown’s bronze statue of Harriet Tubman, followed by a ‘Unity Walk’ around the Park, and culminated in a host of events at Pomona’s Fairplex which included live music, comedy acts, and boxing.

The event was orchestrated by Ray Adamyk, President of Pomona’s Spectra Company, a historic restoration and construction company. Adamyk, working in conjunction with Pomona’s Mayor Tim Sandoval, hosted the event as a part of his ongoing effort to raise three million dollars to restore Salem Chapel in Adamyk’s original hometown of St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada. Late in life, Adamyk uncovered the truth that the Chapel was Tubman’s last stop on her Underground Railroad.

As to how her Underground Railroad that guided enslaved African-Americans ended up all the way in Canada, in 1868, Tubman said, “I wouldn’t trust Uncle Sam with my people no longer. I brought them all clear off to Canada.”

Brown’s statue of abolitionist Harriet Tubman is a powerful statement that has already made a major impact on the Pomona community - demonstrating to everyone the powerful impact that art can make in the community - and how much we hunger for representation. I hope that, in the future, Brown’s artistic vision, her representation of Harriet Tubman, will be more centered in the news features.

That said, the event surrounding the unveiling raises other concerns. The City of Pomona leap-frogged over its own public processes in its introduction of the statue to one of its prominent public parks. Before Pomona’s Cultural Arts Commission and Cultural Arts Citizen Advisory Committee had an opportunity to review the 137 or so artist applications for public art in the city, this one singular application received preferential attention. By disregarding the public process, not only did the other artist applicants receive short shrift, but so did the public-at-large. All were left out of what should have been a very public decision-making process. Though the City of Pomona installed both the Commission and Committee to review all applications, by unveiling the statute before any kind of public review, the City determined that the recommendations of the Commission, the Committee, and its own City Planning Department were essentially irrelevant.

Why this matters is that it is important that our public government remains responsive to public opinion when distributing taxpayer money and resources. In a democracy, it is important that decisions are made by the many rather than the few.

It is even more disturbing that in Adamyk’s interviews on the network news, Adamyk described the ‘Unity Walk’ as not only a walk for people of all races but also as a walk for the police and the community. During this walk, there was a heavy police presence.

I consider the spectacle of this photo-op moment of “community policing” tone-deaf - a whitewashing of Harriet Tubman’s legacy, overshadowing Tubman’s message of abolition. Everyone, including the youth in this community, deserves to learn about Harriet Tubman’s real principles and her opposition to unjust structures of power.

Harriet Tubman, abolitionist and suffragist, believed in direct action. She broke the law and helped fugitives escape. They ran from slave patrols and the police in this country. Born into slavery, Tubman escaped and subsequently made some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved people using the network of antislavery activists and safe houses known as the Underground Railroad. During the American Civil War, she served as an armed scout and spy for the Union Army. In her later years, the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, she guided the raid at Combahee Ferry, which liberated more than 700 enslaved people.

The placement of Tubman’s statue at Lincoln Park holds a certain kind of irony. Though the two were contemporaries, Tubman never spoke with President Lincoln. During an interview for The Chautauquan magazine in 1896, Tubman stated that she did not like Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War days and only learned to appreciate him after her friend, Sojourner Truth, told her Lincoln was an ally:

“No, I’m sorry now, but I didn’t like Lincoln in them days. I used to go see Missus Lincoln, but I never wanted to see him. You see we colored people didn’t understand then [that] he was our friend. All we knew was that the first colored troops sent south from Massachusetts only got seven dollars a month, while the white regiment got fifteen. We didn’t like that. But now I know all about it and I is sorry I didn’t go see Master Lincoln.”

Harriet Tubman’s true legacy is that abolition is an ongoing process and it is from this perspective that the installation of her statue needs to be viewed. Not as a mere gesture at ‘racial reconciliation,’ but as an ongoing effort to make things right.

This most recent walk happened at the same time as the Pomona Police Department continues to target and arrest black youth at a higher rate than their non-Black peers. In 2021, Gente Organizada, located here in Pomona, released a report that 22.4% of youth arrested are Black while only making up 5.6% of the population in Pomona. Black female arrests account for 44.9% of youth female arrests despite only being 5.6% of the population in Pomona. (2)

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Full-length portrait of Harriet Tubman (1820? -1913)

Harvey B.Lindsley 1842-1921 (Contributor)

Matte Collodion Print

This walk happened at a time when protestors fighting for women’s bodily autonomy and reproductive rights faced violence throughout the country. This walk happened as protestors were in the streets of Akron, Ohio because Jayland Walker, an unarmed 25-year-old Black man, was fired at 90 times and struck 60 times by eight Akron Ohio police officers for a traffic violation.

UCLA Professor and Black activist Bryonne Bain tells us, “Los Angeles is ground zero for mass incarceration. With an average of 17,000 people incarcerated daily (as of 2015), LA incarcerates more people than any city in the world. The City of Angels is, in fact, the City of Incarceration.” (3)

According to a recent research initiative by Catalyst California, Los Angeles County’s jail system is the largest in the country. The incarceration rate for Black people in Los Angeles County is 13 times higher than that for white. White people in L.A. County are incarcerated in state prisons at a rate of 1.6 per 1,000, Blacks are incarcerated at 20.8 per 1,000, and Latinos are imprisoned at a rate of 4.3 for every 1,000. Per capita, blacks in L.A. County died at the hands of police more than four times than that of whites in 2015, the project found - and Latinos died at the hands of police nearly twice that of whites. (4)

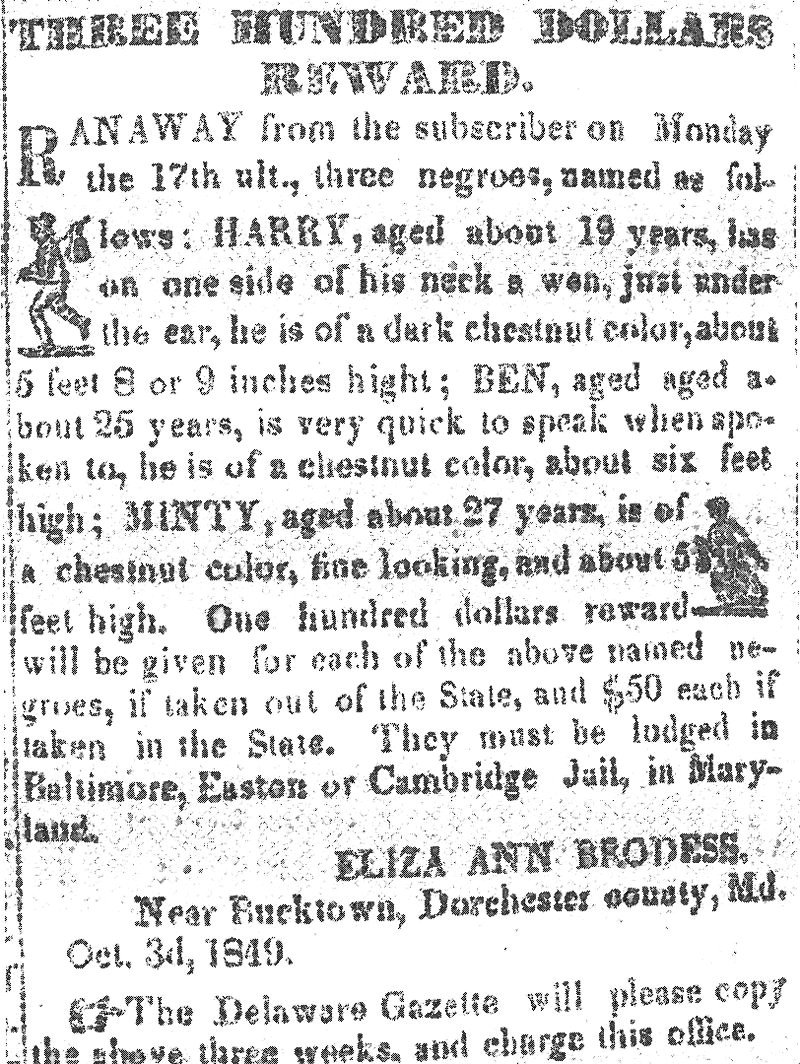

1849 advertisement for the return of “Minty” (Harriet Tubman) and her brothers “Ben” and “Harry,” in which their mistress, Eliza Brodess, offered $100 for each of them if caught outside of Maryland

Per capita, Black people in L.A. County died at the hands of police more than four times than that of whites in 2015, the project found - and Latinos died at the hands of police nearly twice that of whites. (4)

According to the Los Angeles Times: Homicide Report, since 2001, 972 people have been killed by law enforcement in Los Angeles County, according to homicide records from the county medical examiner-coroner. Nearly 80% were Black or Latino. Black people make up less than 10% of LA County’s population, yet they represent 24% of law enforcement killings. White people, who make up more than a quarter of the population, are killed in 19% of the incidents. (5)

Some of us may know police who are very good people (depending on who we are), but it is undeniable that, historically, the systems and structures of police have maintained the status quo in this country. According to the NAACP, “the origins of modern-day policing can be traced back to the ‘Slave Patrol.’ (6)

Policing helped enforce slavery and enforce Black Codes, strict local and state laws that regulated and restricted access to labor, wages, voting rights, and general freedoms for formerly enslaved people. Policing helped enforce Jim Crow laws, upholding segregation. Police have targeted and continue to target Black and Chicano activists. Police have worked against the interests of the working class and poor people.

Pomona does not need to be used as a fundraising and publicity stunt. Pomona does not need the city government and police’s performative gestures. Pomona needs real racial justice and change. Artist voices should be elevated. Pomona schools should have arts equity. How can we develop ways to keep everyone safe? Does this current system of disproportionate funding and support for police meet the needs of the people in Pomona? Harriet Tubman’s legacy needs to be celebrated in authentic ways with the awareness that her mission does not belong to the past, but to the present and the future.

“I was free, but there was no one to welcome me in the land of freedom. I was a stranger in a strange land.”

Abolitionist Harriet Tubman after she made 13 trips to bring 70 enslaved people to freedom beginning in 1849.

Lucia Nagler is a member of the City of Pomona’s Cultural Arts Citizen Advisory Committee, but the opinions expressed here are strictly her own.

REFERENCES

1. Good Day LA. Unity Walk in Pomona ahead of Harriet Tubman Statue Unveil. July 1, 2022.

2. Gente Organizada. Gente de Pomona Equity Report 2021.

3. Bain, Bryonn. 21st Century Harriet Tubman: An Interview with Susan Burton.

4. Los Angeles Daily News: There’s a Huge Race Gap in LA County Incarceration Rates, Study Says. 11.15.17.

5. Los Angeles Times Staff. “Police Have Killed 972 People in L.A. County Since 2000. July 5, 2022

6. NAACP. The Origins of Modern Day Policing. 2022.