I kept being struck by how unfair this was—why was my body changing? How could something that once pulled me strong and true to treetops betray me so terribly? At 9, my breasts started budding, and I was already a head taller and several pounds heavier than the rest of my classmates. My body hair turned from golden to dark black and seemed to cover me all over. I had stretch marks across my hips, legs and breasts. I felt like a werewolf mid-transformation. I felt alien and wrong. My children’s clothes did not protect me from the adults who sexualized my body. Men would call out vulgarities from cars, honking their horns as they whistled at me and my light up shoes, my sequined Bobby Jack sweater. At this point I was already a sexual abuse survivor as well, and this new body frightened me to no end. I grew my hair long and wore it down. I lived in oversized sweaters year-round, trying fruitlessly to hide in the fabric. This shame I felt about my developing body extended to shame about my ethnicity as well. Which I also tried to hide.

I developed a healthy amount of internalized racism that manifested in lies to classmates: I was half Italian in grade school, born in Italy in high school. I lied about who I was, where I came from, to try to distance myself from the way I saw my mother treated. I was terrified of ending up like her, a beautiful strong honest woman who was pregnant at a young age and shackled to a full-time warehouse job. I didn’t want to putter around the house, spending all of my free time cleaning up after everyone else. The more I distanced myself from my heritage, the more I assimilated I became the more control I felt over my future. The less Mexican I felt, the less indebted to these sexist traditional ideals I felt. I hated the assumption that I would get married, have children, and serve them all a plate before I sat down. I hated that family would ask me about prospective boyfriends before prospective colleges. I hated being delegated to housework when none of my brothers had to so much as wash a dish. I love my family, and owe my life to them, but the sense of duty that hung over my head was suffocating. Once in high school, I joined marching band, pride club, yearbook—desperate to find obligations and responsibilities at school that could act as fuel on my rocket out of town. The sense of duty I forged, independent of my assigned gender or ethnicity, wholly dependent on my skill and talent, felt earned instead of inherited. It was hard not to feel resentment towards my culture, especially since representation was few and far in-between.

Our Mexican culture exists in liminal spaces—on the car radio, on television, at certain markets or family parties. We have to extend our hands, and ask for bits of Mexican culture, as we seep in American ideals. Although Latinx people were all around me growing up—both in the towns I lived and at school—I never saw them in positions of power. I went to school in Pomona, Ontario, and Chino where all of the teachers I had were white up until college. I didn’t know any whose parents went to college. Parents in our neighborhoods were forklift certified, employed at the various warehouses that continue to pollute communities in the Inland Empire and San Bernardino County. Those of us who expressed interest in higher education were encouraged to seek out practical careers. Many went to vocational schools and became nurses and dental assistants, drawn to a steady paycheck with unwavering demand. Artists, writers, and those of us with stars in our eyes were met with much less support when expressing pursuing things related to the arts. This was seen as a waste of opportunity and potential. My mother hardly spoke of her time in Mexico, but she would often remind us of the struggles she faced to get to school, telling us of the miles she’d trek in the early morning while the sun still slept behind the horizon. Sacrifice, guilt and the shouldering of burdens seemed to be the only constant in our culture, the only things taught.

Although Spanish was my first language, it quickly felt clumsy and heavy on my tongue, worn away by lack of practice or immersion. As my mother’s first born, I have been her translator since grade school, sitting in on phone calls to bill companies, performing alchemy with each whispered word. I’ve witnessed firsthand how quickly patience is lost if you don’t speak the same language. Ditto if your accent is too heavy. I quickly understood that English was prioritized in every conversation, often with little to no Spanish alternative. English became my best subject, a strength hewn by a love of reading born of my mother’s bedtime stories. Meanwhile my Spanish has stuck around conversational grade school level. I can read, if I take my time and sound out each word but can’t write much, at least not confidently. I’m grateful for the scraps I have, since a few of my younger brothers, like many other Latinx first and second generations, can’t speak Spanish at all. Language, like any living thing, must be nurtured and shown love or, like any living thing, it can die. Many families don’t speak Spanish because their grandparents had their knuckles rapped by wooden rulers for every word spoken at school or church. In my neighborhood, foreign languages only mattered on high school transcripts and resumes for part time jobs at the mall. In the real world, no one gives a fuck if you speak Spanish. Value, love and appreciation for our culture must be taught or this world makes us forget, or worse—assimilate.

High school was a major turning point for me. My involvement with marching band and various clubs meant I was on campus often, granting me freedom to find myself. It was my involvement with the pride club in particular that spurred my self-discovery, starting first with the realization that I was not merely an ally, but a member of the community. The more I was able to immerse myself and learn about queer culture, the more confidence I built. Our advisor was wonderful, taking the time to not only teach us about the various categories and labels in the queer community, but queer history through film and documentaries. Even though there was no singular person we learned about that matched my identities exactly, just learning about queer existence was enough to propel me to seek out more. I was delighted to find instances of queer Mexican people and communities especially, their sheer existence a radical act of resistance against our staunchly traditionalist culture. Finding representation and validation in gender nonconforming behavior throughout Mexican indigenous cultures, like in the Zapotec culture of Oaxaca where the muxe reside was life changing. The more I widened my understanding beyond the American and colonized paradigms I was taught and the more I was able to connect to my culture, and ultimately with myself.

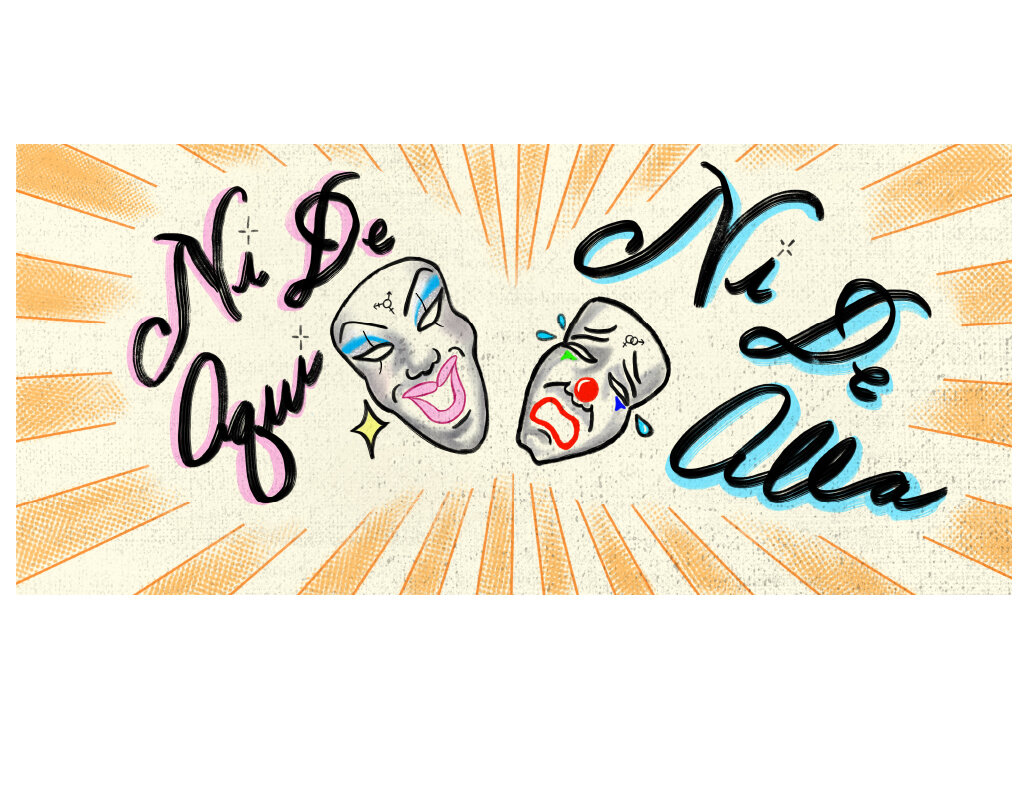

I’m queer, nonbinary and Xicanx, identities that exist in liminal spaces, in the in-between, ni de aqui, ni de alla. I’ve spent so long reciting the ways these identities cancel each other out, that I thought someone like me was not allowed to exist. I thought the combination of these identities would make all of them invalid, leaving me with nothing. I thought I was an oxymoron, a negative zero, my string of identities shining like fake pearls around my neck, betraying my secret to the world before I had a chance to figure out who I was. Now I wear them with a newfound pride forged with the help of community, advocacy and intersectionality. I still don’t know exactly where I fit, but now I know that I can make room.

I’ve always felt different. But now, I no longer feel wrong.

L.V. Loya Soto is a writer, multimedia journalist, and artist from California. they are a magazine and opinion writer, with a passion for the radial impact of immersive storytelling.